If you stand on a warehouse floor long enough, you’ll hear the same phrase: “It’s just stacking boxes.” But anyone who has worked in outbound fulfillment knows that store-ready palletizing is governed by a surprisingly intricate hierarchy of business rules — rules that keep operations efficient, safe, and compliant.

These rules determine how pallets move through the retail floor, how quickly drivers unload on multi-stop routes, how much rework associates must do, and whether products arrive undamaged. They are central to day-to-day warehouse performance — yet they’re also where traditional automation falls short.

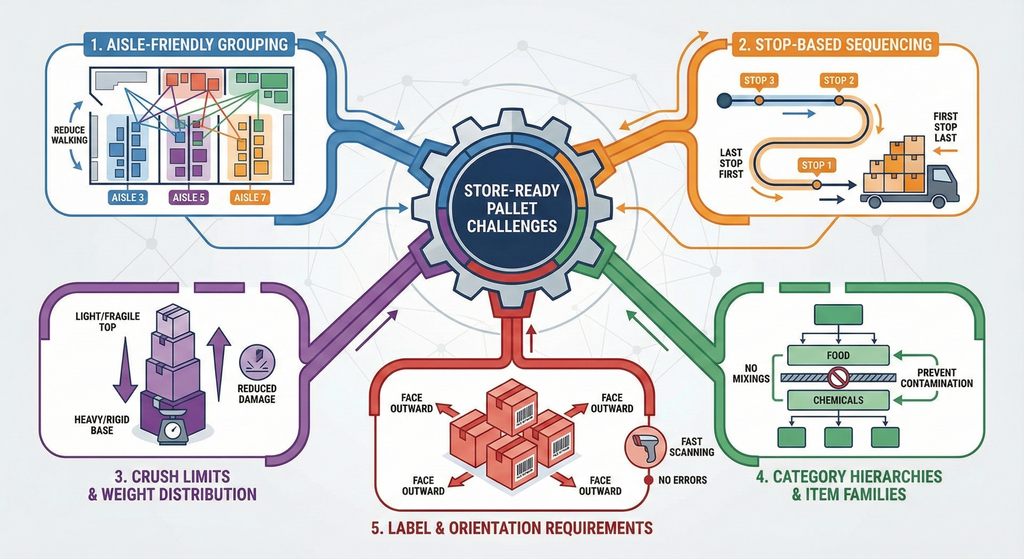

Below are five of the most common rules warehouse teams enforce every day, why they matter, and where they appear across industries.

1. Aisle-Friendly Grouping

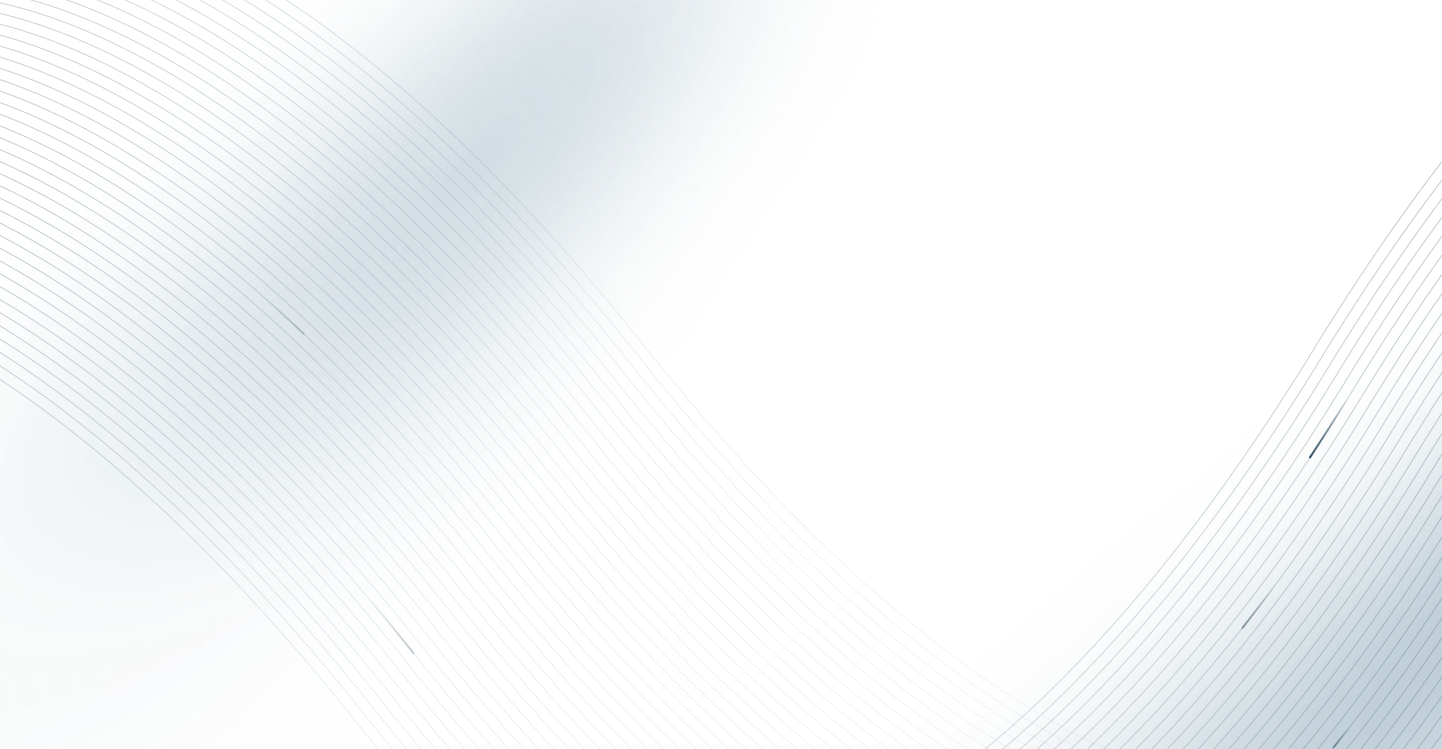

Aisle-friendly grouping means organizing cases on the pallet according to where they belong in the store, so items destined for the same aisle or section are placed near each other. You’ll see this everywhere in grocery and mass retail, where high SKU variety makes fast in-aisle replenishment essential; in DIY and home improvement, where products are tightly mapped to aisle layouts; and in club stores, where efficient shelving is a major driver of labor productivity.

- Why it matters: It reduces walking distance for store associates, speeds replenishment, and minimizes resorting on the retail floor.

2. Stop-Based Sequencing (for Multi-Stop Routes)

Stop-based sequencing arranges the pallet so that cases for the last delivery stop are loaded first and the first stop is loaded last — enabling fast, clean unloads at each drop. This rule is foundational in grocery distribution, where drivers may service several stores in a single run; in 3PL networks, where multi-drop routing is the norm; and in foodservice, where restaurants or institutional kitchens expect precise, rapid unloading.

- Why it matters: It reduces driver labor, prevents mis-deliveries, and keeps route schedules on track.

3. Crush Limits & Weight Distribution

Crush limits and weight distribution rules ensure that heavy, rigid items form the base of the pallet while lighter, fragile, or crush-sensitive items sit above. These rules are universal across grocery, where cereal or bakery goods cannot go under liquids or canned goods; pharma and OTC, where packaging tolerances are strict; and e-commerce fulfillment, where packaging variation makes protection

especially important.

- Why it matters: Proper weight distribution prevents damage, maintains pallet stability, and reduces shrink.

4. Category Hierarchies & Item Families

Category hierarchies govern the allowed order of product families — for example, detergents must sit below food items, poultry below beef, or liquids below dry goods. These constraints are essential in fresh food, where food safety rules dictate strict handling hierarchies; in CPG, where separation between chemicals and edible goods prevents contamination; and in pharma, where product families must be physically ordered to meet regulatory expectations.

- Why it matters: They prevent contamination, maintain compliance, and reduce store-level rework.

5. Label & Orientation Requirements

Label and orientation rules ensure barcodes and branding face outward for scanning and presentation. They’re prevalent in retail and grocery, where receiving relies on fast scanning; in pharma, where traceability is critical; and in beverage distribution, where brand-facing presentations are often required.

- Why it matters: They reduce scanning errors, speed receiving, and support merchandising standards.

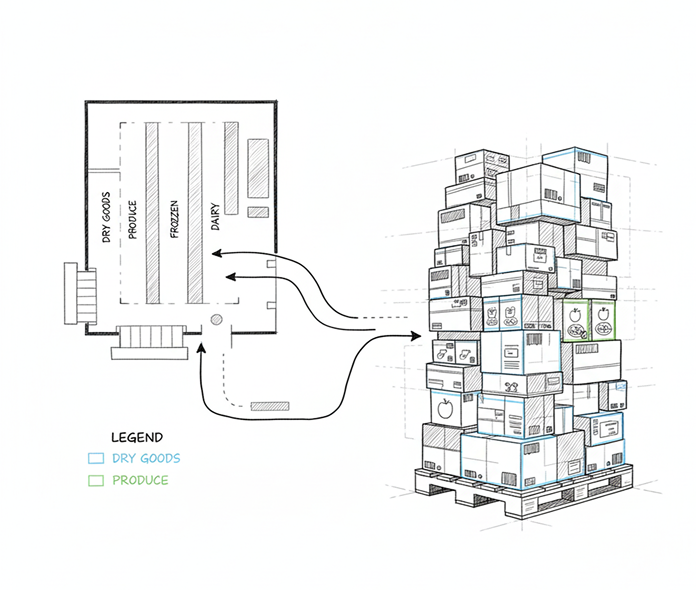

The Real Challenge: Why Traditional Automation Required Perfect Sequencing

Once all these rules are layered together, choosing the “right” next case placement becomes an enormous computational problem. Every decision affects the next several layers, and every rule must be satisfied simultaneously.

Historically, automation vendors solved this by assuming perfect sequencing upstream: cases must arrive at the palletizer in exactly the order they should be placed. To make that possible, integrators built large-scale sequencing infrastructure — AS/RS systems, shuttle buffers, conveyor accumulation lanes, and orchestration software designed to feed robots an idealized, pre-arranged case order.

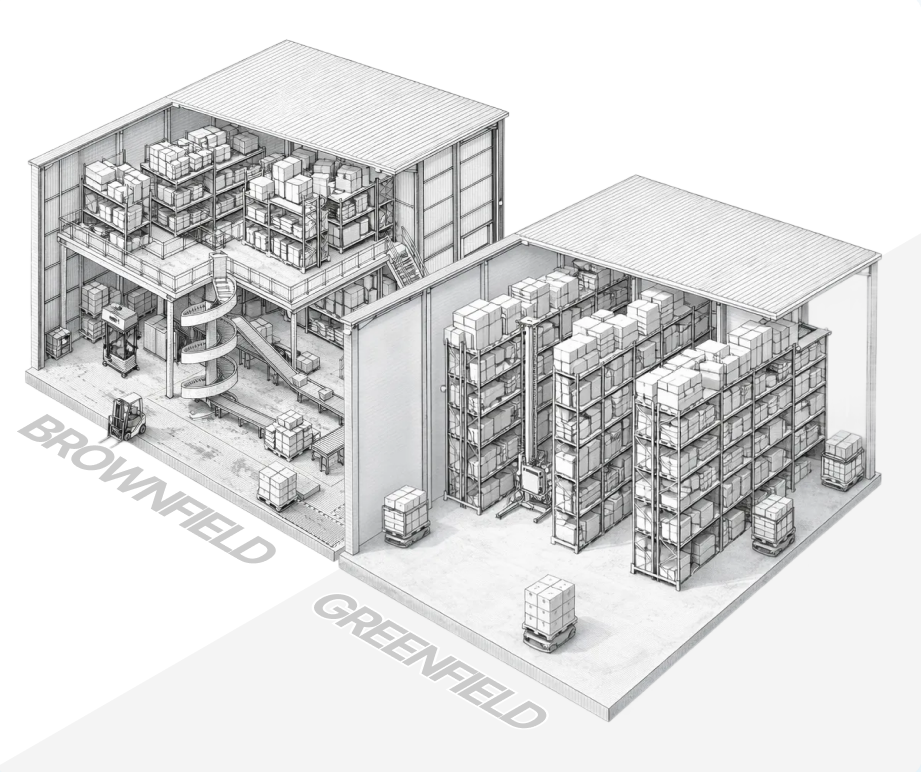

These systems work, but they’re expensive, brittle when flows drift, and impractical for the vast majority of brownfield warehouses, where case arrival is messy, variable, and shaped by real operations, not perfect algorithms.

Why Humans Don’t Need Perfect Sequencing and Where Jacobi’s OmniPalletizer Fits

A human pallet builder doesn’t stop when items arrive out of order. If they receive eggs before bricks, they simply place the eggs to the side, continue stacking heavier items, and bring the eggs back in when it makes sense. That tiny act — a lightweight mental model combined with a small physical buffer — is what allows humans to keep the workflow moving while respecting all business rules.

Jacobi’s OmniPalletizer brings that same human-like flexibility into automation. Instead of depending on massive sequencing systems, it uses small, dynamic robotic buffers that temporarily hold cases until the right stacking conditions appear. This allows the system to:

- absorb real-world, unsequenced case flow.

- respect all operational rules in real time.

- avoid brittleness when arrivals are imperfect.

- operate reliably in brownfield environments without requiring AS/RS-scale infrastructure.

It’s a middle ground: the adaptability of a human pallet builder with the consistency and predictability of automation.

Why It Matters

Most warehouses don’t run in perfect order — and automation shouldn’t require them to.

The real operational impact comes from systems that can handle aisle logic, stop sequencing, category hierarchies, crush limits, and orientation rules without forcing a building redesign or a massive sequencing investment.

Jacobi’s OmniPalletizer unlocks that shift: automation that adapts to operations, not operations that must adapt to automation.