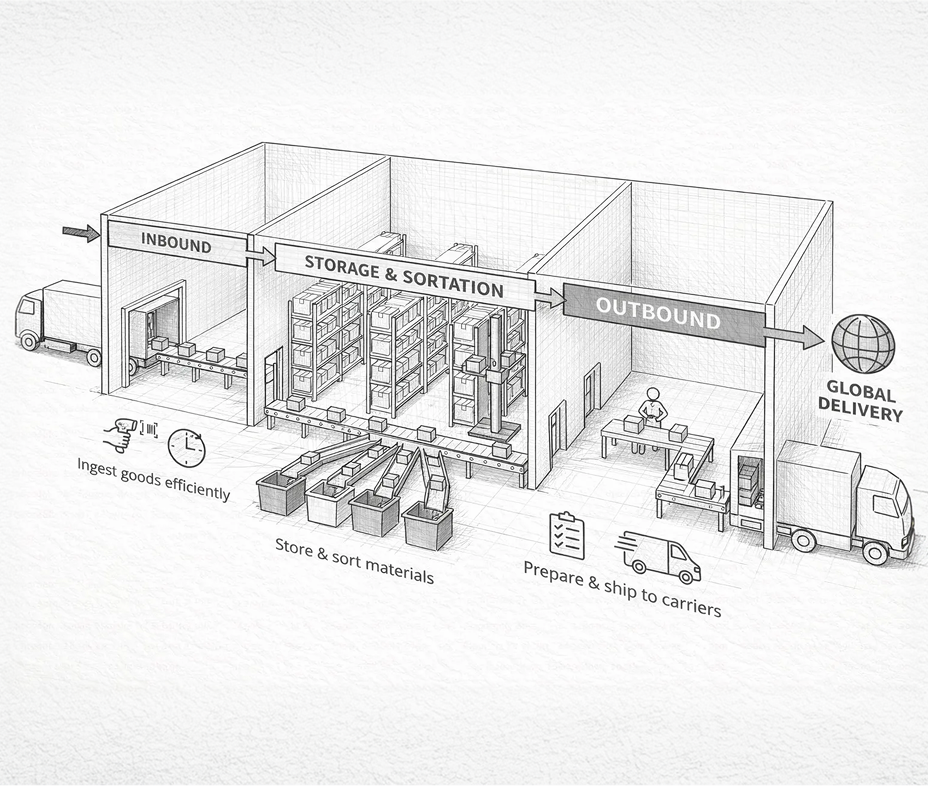

Walk through a modern distribution center and you will see pockets of impressive automation—sortation, scanning, putwalls, goods-to-person, dense storage. Then you reach the dock edge and the “last meter” of many outbound workflows: building pallets that can survive transport, match store needs, and leave on time. In a surprising number of sites, that step is still driven by manual labour, improvisation, and workarounds.

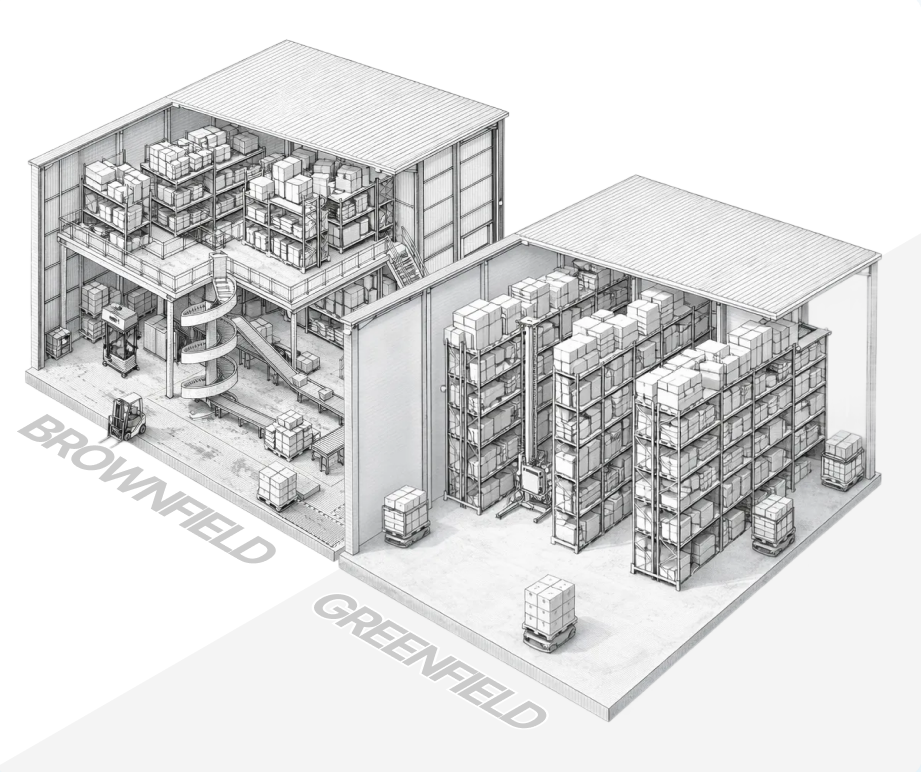

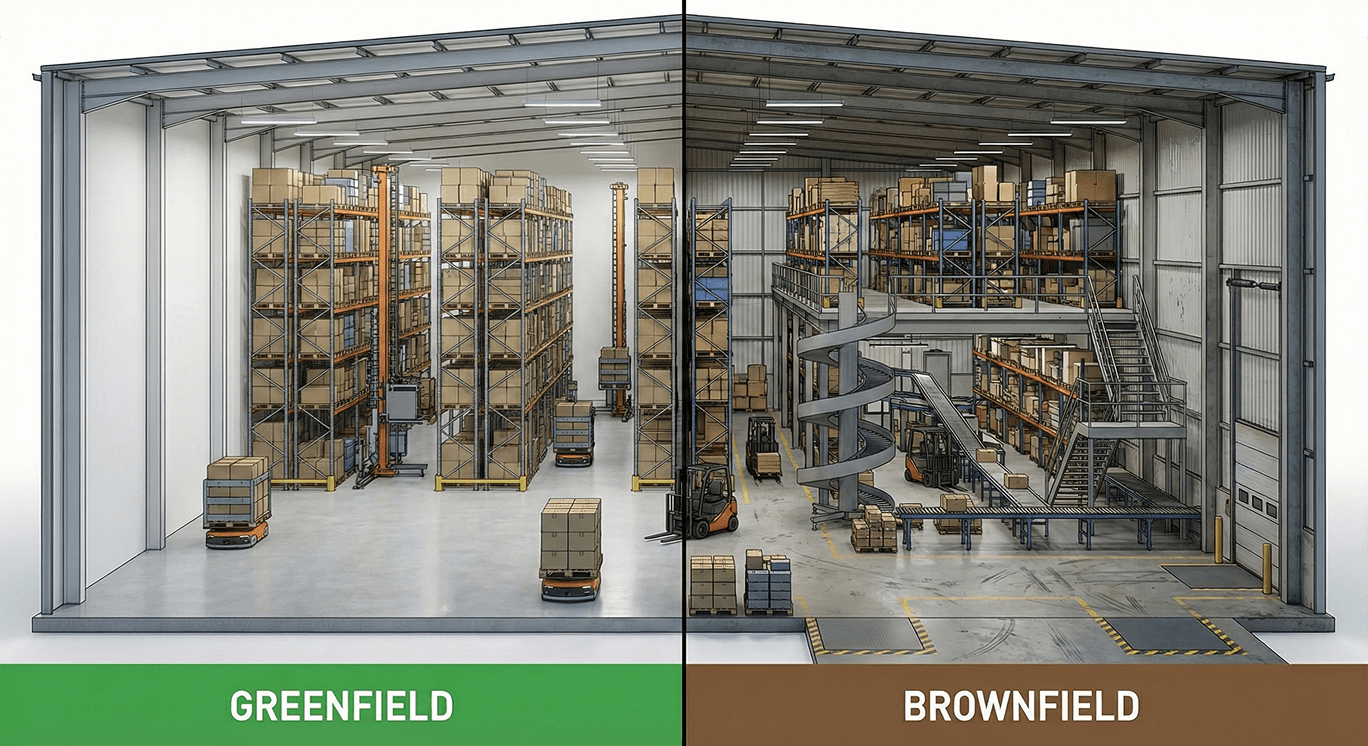

The reason is not that warehouse leaders “haven’t modernized.” It’s that most warehouses are brownfield by default: live buildings with legacy layouts, sunk infrastructure, and operating constraints that make clean-slate automation assumptions fail. Solutions designed for greenfield conditions often look elegant on paper, but they collide with the reality of space, variability, uptime, and change management.

The warehouse you actually have

A greenfield site is designed around automation. A brownfield site is designed around whatever the business needed at the time: a conveyor extension added after peak season, a mezzanine built to create pick faces, a dock re-striped to fit a new carrier, a WMS customised over years. The result is not “messy” in a pejorative sense—it is a rational accumulation of decisions made to keep service levels high.

That history creates two hard truths:

- You cannot stop the building. - Most facilities have limited downtime windows, and even short outages can cascade into missed loads and customer penalties.

- Your constraints are site-specific. - Two warehouses with the same throughput can have entirely different pinch points because of dock geometry, labour model, upstream systems, and SKU mix.

This is why “copy-paste automation” is rare in brownfield environments, even within the same network.

Brownfield constraints that break automation assumptions

Brownfield automation fails most often when a design assumes one of the

following is “easy”:

- Space is available where you need it. - In reality, the valuable space is already allocated—to accumulation, staging, returns, value-add, damaged goods, or simply safe travel aisles. An automation island that needs a large footprint may be technically feasible and still operationally impossible.

- The flow is orderly. - Many outbound operations see lumpy “waves” of cases, gaps, bursts, and last-minute prioritisation changes. What looks like a stable average rate can hide peaks that define the real requirement.

- Exceptions are rare. - Overweights, damaged cartons, label issues, short picks, out-of-stock substitutions, and vendor packaging changes are daily events. People handle this with judgment and informal buffers; automation must have an explicit plan.

- Integration is trivial. - A brownfield site often involves multiple control layers (WMS/WES/PLC), bespoke rules, and legacy equipment. Integration is not only “connect the signals”—it is aligning automation behaviour to how the site actually runs.

- Labour is the only objective. - Operators also care about trailer utilisation, pallet quality, store readiness, safety, and throughput during peaks. Any automation that improves one metric while degrading another will be rejected in practice.

Why big-bang projects feel brittle in brownfield operations

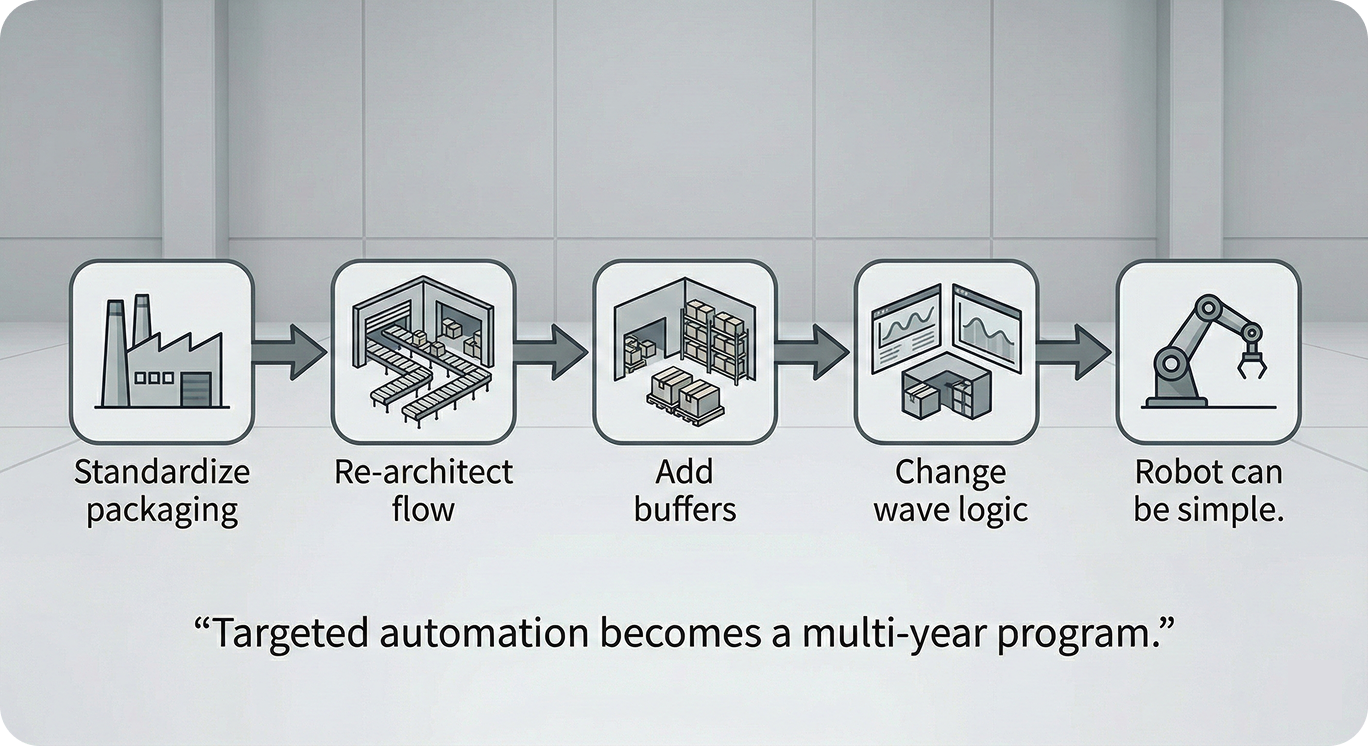

Brownfield leaders tend to be risk-averse for good reasons. A “big-bang” conversion concentrates risk into one event: if commissioning slips, or performance misses, or edge cases accumulate, the site loses flexibility exactly when it needs it most.

The operational preference is typically the opposite:

- Start where the pain is highest.

- Keep fallback options.

- Prove performance with real data before committing.

- Expand incrementally once the change is stable.

This is less about conservatism and more about protecting service levels in an environment where variability is a feature, not a bug.

What “brownfield-native” automation looks like

Brownfield-native automation is not a single technology choice. It is a deployment philosophy that respects the constraints above.

In practice, it tends to share four traits:

- Fits into existing lanes and layouts. - Instead of demanding a rebuild, the automation drops into what already exists—conveyor lanes, dock-adjacent areas, or defined handoff points—so the rest of the building can keep operating.

- Coexists with manual work. - Brownfield success often depends on graceful coexistence: manual stations for exceptions, the ability to bypass, and a practical ramp-up plan. This preserves operational flexibility during peak periods and early adoption.

- Handles real case flow. - The automation must tolerate imperfect sequencing, arrival “lumps,” packaging drift, and rule collisions without requiring the site to behave like a lab.

- Is proven before it becomes mission-critical. - The most reliable way to de-risk is to validate throughput and pallet quality using the site’s real SKU history and flow patterns in a digital twin—then deploy the same planning logic in production so expectations match reality.

A practical way to evaluate a brownfield automation idea

When assessing an automation concept in an existing warehouse, a useful

checklist is:

- Where does it sit physically, and what gets displaced? - (Staging, travel aisles, doors, accumulation, safety zones.)

- What happens during peaks, not averages? - (Wave releases, late orders, carrier cut-offs, seasonal spikes.)

- What is the exception path? - (Damaged cartons, no-reads, oversize, priority changes.)

- Can the site fall back without chaos? - (Bypass, manual mode, partial operation.)

- How will you prove it before committing? - (Data-driven simulation, clear acceptance criteria, measured ramp.)

If an idea has weak answers to any of these, it is not necessarily wrong—but it is likely a greenfield design being forced into a brownfield reality.

Conclusion

Most warehouses are not “designed” for automation because they were designed for something else: shipping reliably under changing business conditions. Brownfield constraints—space, variability, exceptions, integration complexity, and zero-tolerance for downtime—are the real reasons many automation projects stall or overreach.

The path that works in most existing sites is pragmatic: modular deployment, coexistence with manual operations, and evidence-based validation using real data. That is how automation becomes an operational upgrade instead of a high-stakes experiment.

Where OmniPalletizer and modern 3D vision fit

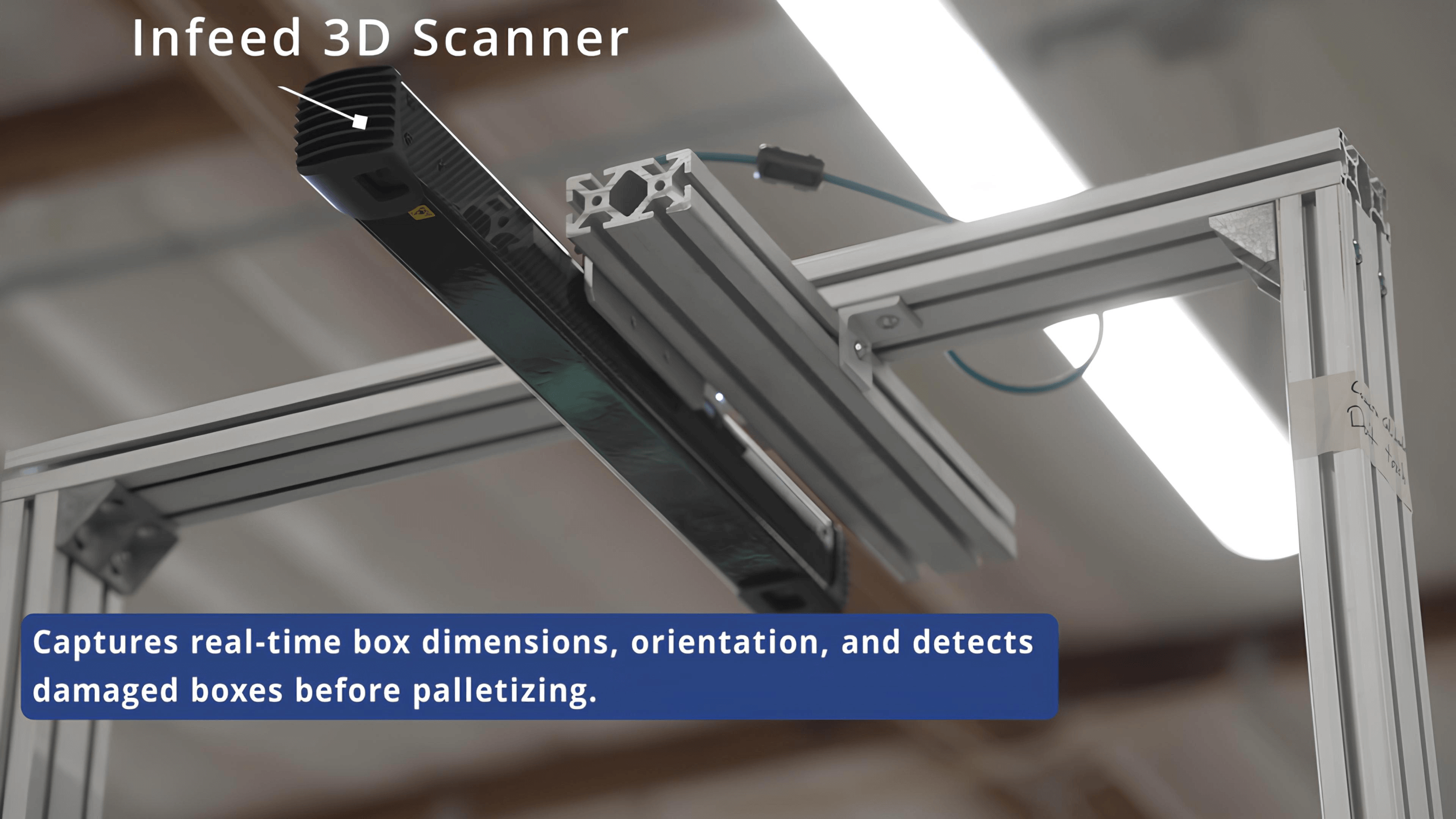

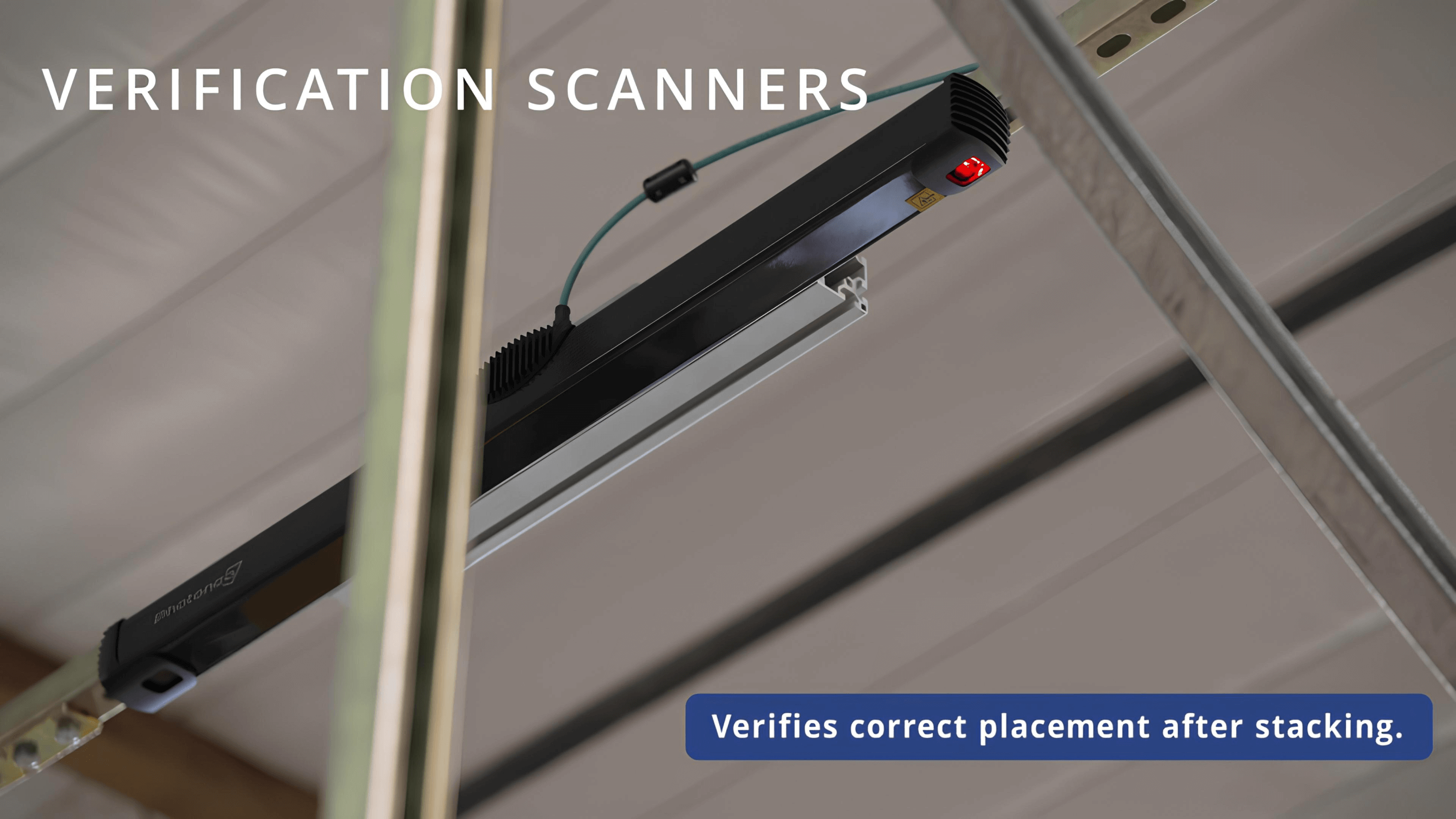

Jacobi’s OmniPalletizer is built for this brownfield reality: a modular approach that can drop into existing operations, adapt to real case flows, and be proven in a digital twin before production rollout. But brownfield resilience is not only about planning—it is also about perception. In the real warehouse, you rarely get perfect upstream data: cases arrive with drift, labels are imperfect, packaging changes, and pallets are never exactly where they “should” be.

This is where modern 3D vision becomes an enabling layer. High-fidelity 3D cameras—such as Photoneo’s—act as “eyes in the warehouse,” giving robots a reliable, geometric understanding of what is actually in front of them, in real time. That perception layer lets automation behave more like experienced operators do: reacting to the physical world as it is, not as a clean database says it should be. Combined with a brownfield-native palletizing brain, 3D vision is one of the most practical ways to bring intelligence into existing warehouses without demanding perfect conditions first.