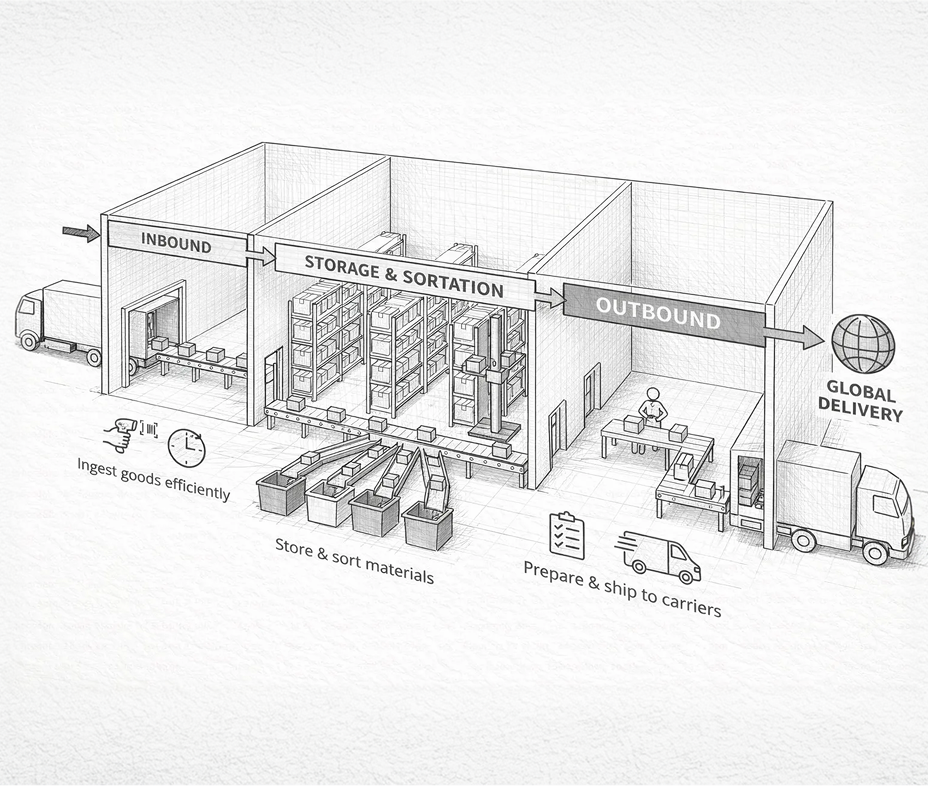

Walk through almost any distribution center and you will see impressive automation—high-speed conveying, sortation, goods-to-person, scanning and weighing, even automated storage. Then you reach the dock edge, where orders become pallets. In many operations, that last step is still manual, labour-intensive, and treated as “just part of warehouse life.”

That disconnect is not a footnote. It is a structural automation gap: mixed-case palletizing. It is one of the most common, most physically demanding, and most operationally consequential workflows that still relies on people—especially in outbound store replenishment and high-variability case handling.

Mixed-case palletizing defined and why it matters

Formally, mixed-case palletizing is the task of building a pallet from a stream of different SKUs—different weights, dimensions, packaging types, fragility, and handling constraints—while meeting the rules your network actually runs on. The rules vary, but the intent is consistent: stable pallets, good cube utilization, and minimal downstream rework.

Mixed-case palletizing is not one niche use case—it is a recurring pattern that shows up wherever outbound loads must be usable, not merely complete:

- Retail and grocery distribution - aisle-friendly store pallets, temperature-zone mixes, stop-sequence logic, and constant vendor packaging drift.

- CPG / FMCG manufacturers - dense replenishment pallets from mixed orders, with frequent promotional assortment changes.

- 3PLs and LTL providers - multi-client order profiles and changing load plans, where poor pallets translate directly into rework and freight cost.

- E-commerce fulfilment and pharma - extreme SKU variability and unpredictable order patterns, often with handling constraints that are non-negotiable.

This is why mixed-case palletizing is a “missing piece” problem: it sits at the intersection of variability, rules, and real-time execution.

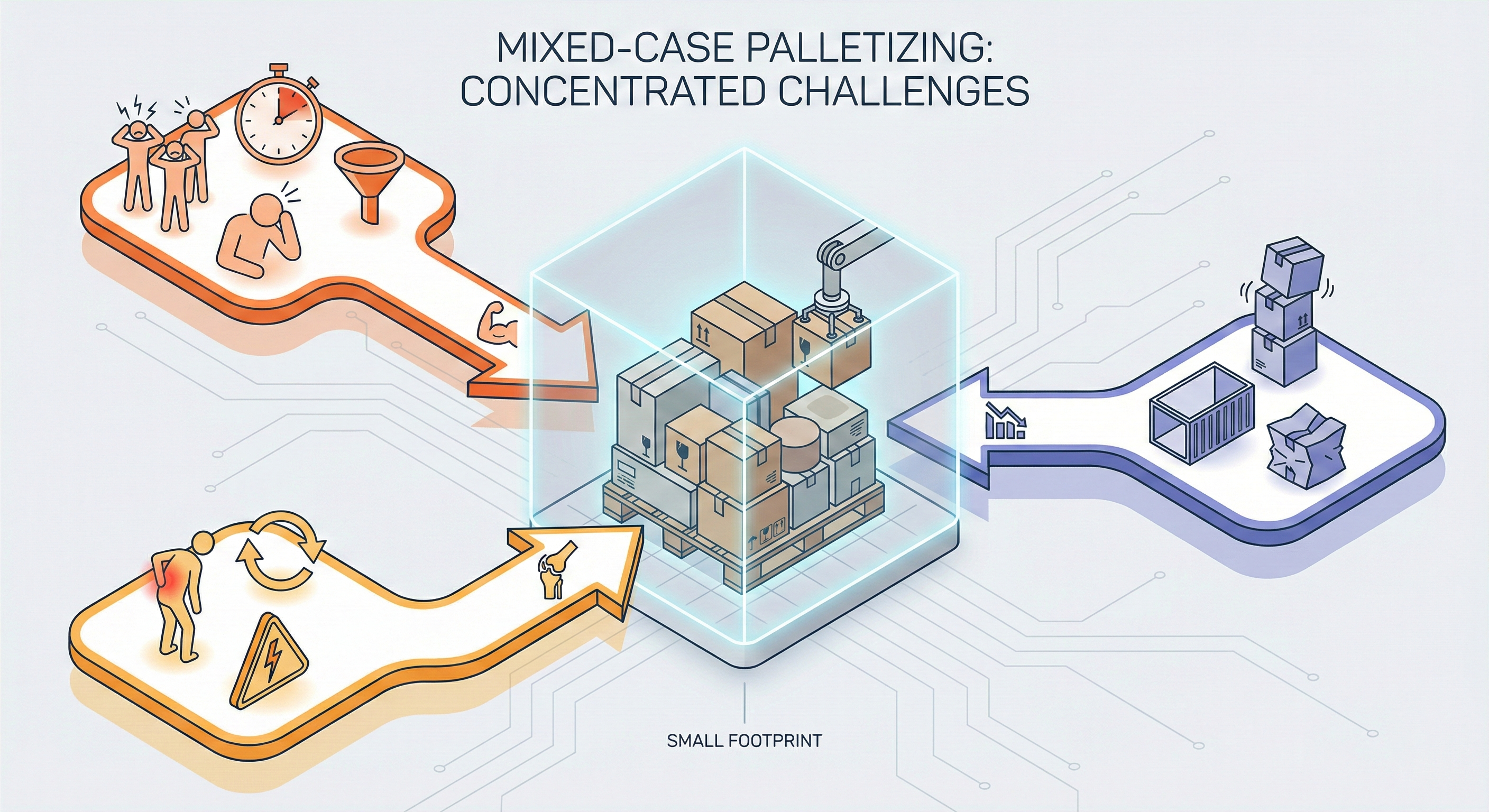

Mixed-case palletizing concentrates several hard problems into a small footprint:

- Labour bottlenecks and peak pain - The hardest positions to staff often sit exactly here—manual pallet building and late-wave outbound, where peaks are unforgiving.

- Ergonomics and injury exposure - Heavy lifts, awkward reaches, and repetitive motion accumulate quickly across a shift.

- Freight and space efficiency - Poor stacks are not only a damage problem; they also lower trailer utilization and create rework that steals capacity.

The net effect is that the last 10 feet of the process can dictate the performance of the entire outbound system.

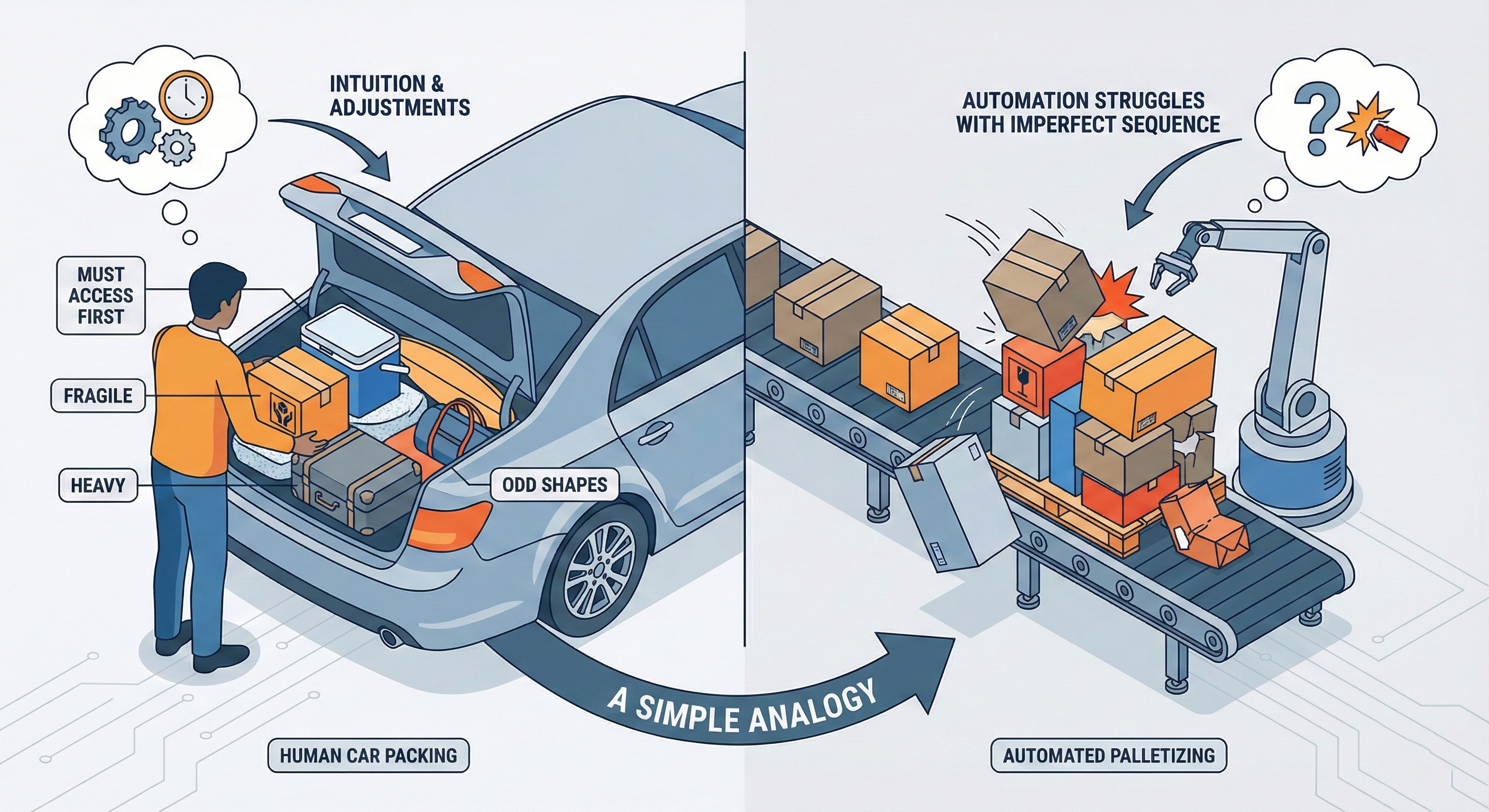

A simple analogy: packing a car, not stacking identical crates

If you have ever packed a car for a long trip, you already understand the essence of mixed-case palletizing. You do not just load items in the order they arrive at the garage door. You constantly trade off constraints:

- heavy items low (stability),

- fragile items protected (damage),

- “must access first” items near the top or the back (stop order / store presentation),

- odd shapes that force compromises (packaging variability),

- and the fact that you are packing while time is running out (peak throughput).

Humans solve this with intuition and micro-adjustments. Automation struggles when the incoming sequence is imperfect and constraints collide.

Why traditional automation struggles

For years, the common path to automating high-variability pallet building relied on a hidden assumption: perfect sequencing. In other words, cases must arrive at the palletizer in an order that already makes a good pallet possible, with buffers and orchestration upstream to enforce it.

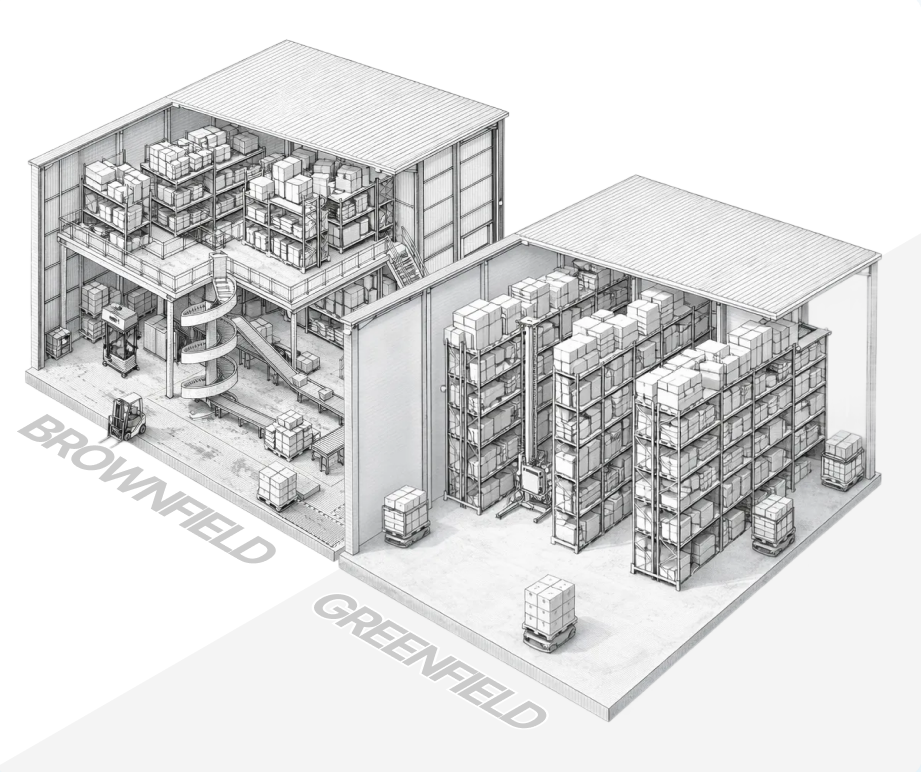

That model tends to pull the project toward “mega-project” dependencies—significant buffering, tightly controlled material flow, and large system changes. In many warehouses, that is not feasible without major disruption or capital expenditure, which is why historically only a small fraction of sites could justify the approach.

Meanwhile, real operations are full of variability: lumpy waves, SKU proliferation, packaging changes, and imperfect arrival patterns. Even when the upstream systems are sophisticated, the case flow arriving at pallet build is often “good enough for people,” but not good enough for brittle automation.

What “good” looks like

A useful way to evaluate mixed-case palletizing is to ask three plain questions:

- Does it respect the operational rules that matter most? (e.g., heavy-to-light stacking, crush limits, aisle grouping, stop sequencing).

- Does it keep up with peaks when the case flow gets messy?

- Can you prove performance before you disrupt the floor? In practice, that means using real SKU history and real arrival patterns in simulation to align expectations with reality.

If any of those are missing, adoption becomes a high-stakes experiment—exactly what operations leaders are trained to avoid.

Takeaway: a category worth naming

Mixed-case palletizing is not a rounding error in warehouse automation. It is a foundational workflow that determines labour intensity, safety exposure, outbound stability, and freight efficiency—and it is common enough that nearly every operator and integrator will recognize it once it is clearly scoped.

Jacobi’s OmniPalletizer is designed for this specific gap: building mixed-case pallets from live case flow (pick-to-belt, goods-to-person, AS/RS, e-commerce fulfillment, case pick, etc.), while enforcing the rules operators care about—heavy-to-light stacking, crush limits, aisle-friendly grouping, and stop-based sequencing—without requiring upstream sequencing infrastructure or a building redesign.